One of the hardest things I’ve seen people struggle with is their cognitive incapacity to realize someone else they’re talking to is NOT understanding what they’re saying, and that the target of the communication likely cannot understand. People, of course, want to map this kind of miscommunication to subject matter. I have a Ph.D., I did my research in chaos theory, so therefore if I talk to someone about chaos theory, they won’t be able to understand what I’m talking about because THEY don’t have a degree in engineering.

Of course, this does indeed happen. If you write a thesis on chaos theory, you’ve hopefully gotten a reasonably sophisticated understanding of the ins and outs of said theory. Unfamiliar words, like bifurcation, limit cycle, attractor and so on will likely cause confusion for a lay person, not grounded in advanced mathematics.

But I also ascribe to the viewpoint “if you can’t explain your research to your grandma, you likely don’t understand it very well yourself.” What that really means is very different. It means you ought to be able to take what you’ve done and analogize it so that a non-specialist can generally get the gist of what you’ve spent 3 years sitting in front of a computer doing.

Sometimes, topics are so convoluted, that’s not even possible. But I’ve found that most subjects are not so weird that if you practice analogizing, you can spin a narrative that grandma can grok.

All that’s well and good. You SHOULD be able to take whatever it is you do and at least have as a goal that people can modestly understand some complicated, multivariate process that you need to explain. At least with you in the room, and connecting to the people you’re explaining it to. We do this all the time in engineering education. Young people aren’t raised on concepts like entropy and enthalpy, of course (and probably not most readers of this blog!) But when you’re navigating complex issues (like whether COVID was invented in a lab) with multiple twists and turns, that contradict the mental models that people have on how the world is supposed to work, things get more challenging.

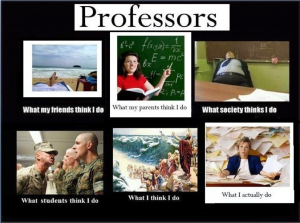

An example is in order. Let’s talk about my job as a professor. One of my favorite multi-panel pastiches is below. It’s wildly accurate on how people perceive my position.

There are multiple versions of this meme. Here’s another one.

Or this one… (you have to have some deep memory to get all the frames on this meme…)

It IS true that (at least before the Age of Laptops) that most of what I did was pushing some version of paper around. Now, of course, I push the electronic version. Last week, for example, I had to confirm for one of my grants that I had not stored nor kept any equipment from a given project (the sponsors take my word for it!) that should have been returned THREE YEARS AGO. I’m lucky if I can remember what I had for breakfast — not the equipment requirements for one of about 80 projects I’ve had in the meantime.

But even that doesn’t convey the actual complexity of my job. Let’s say I write a grant to the National Science Foundation (NSF), the branch of the federal government that hands out money to people like me to do research on things various people might, temporarily, consider to be VERY IMPORTANT as an up and coming area of national interest. I, as an expert in something, am supposed to be paying attention to announcements from the NSF, where Very Smart People have figured out what we’ll need to know in the future. And then pay people like me, or rather have people like me pay graduate students to actually figure out that knowledge so the national interest is served.

On the surface, this seems reasonable.

- VSPs figure out where our knowledge deficit is.

- They publish a Request for Proposals (RFP) .

- I read the RFP, and think I have some ideas that might help.

- I write a proposal to NSF.

- NSF reviews my proposal, along with others, and then gives me (hopefully) the money.

- I supervise the graduate students who then generate the knowledge.

- We publish the knowledge in journals, where other scientists have reviewed our work to make sure it’s right.

- Science, my career, and life march on!

All this maps to what I would call a meta-linear progression that would make sense to most people. Except, of course, it’s not how it works at all.

It’s not impossible to draw a block diagram of how this ACTUALLY works. But it would be complicated. And what are the complicating factors?

- In order to have any hope in hell of getting the money for a given RFP, I likely have to have something like 50% of the work already done that I might propose.

- I might have participated, if I have a close relationship with NSF and the program manager, in constructing the RFP, so there are potential (but never acknowledged) conflicts of interest in getting the money.

- If I’m reading the RFP for the first time, the odds are I could never write a competitive proposal, because NSF really only funds mostly incremental research that will only stretch out about 1-2 years in the metacognitive space.

I could go on. There are also memetic forces inside the agency I’ve written about here that make the agency resistant to funding any truly innovative work at all. All this is counterintuitive, and in a complicated and complex fashion, have most people either a.) rubbing their heads in disbelief, or b.) assuming there’s a conspiracy afoot to make us all stupid.

In order to actually believe what I’ve written, you’ll either need some grounding validity experience yourself in the process, meaning you’ve written proposals to NSF that alternately were or were not funded, you think I’m a sour grapes kook that hasn’t had much luck with NSF funding (kinda true) or you’ve lost the plot and thrown all this into the ‘government is a fucked up conspiracy anyway’ bin.

Here’s the point. Somewhere along the plot line, unless you’ve had a lot of experience with NSF (as I have) you hit your complexity limit. You had likely a straightforward interpretation of how things work in getting a government grant, and when I started loading all the other stuff in the hopper, you got lost (or you didn’t care.) In short, I lost you. Either the story itself wasn’t so great (very possible) or my authority on the issue, in your mind, was weak, and so you just flushed the whole thing down the garbage chute.

The knowledge structure work that I’ve done can help you understand this — here’s a recycled picture.

Short answer — once we get off that relatively straight line progression, most humans hit complexity limits relatively quickly.

What’s the takeaway? All we have, especially when communicating with the public, is to remember the straight line principle. Make sure to use models that people understand when making analogies, especially when blended into narratives.

Or you’ll lose virtually everyone.